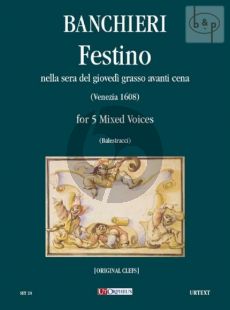

Il Festino nella sera del giovedì grasso avanti cena by Adriano Banchieri (1568-1634) was published in Venice by Ricciardo Amadino in 1608 in five part books (Canto, Canto II, Alto, Tenore, Basso) without a score, as was customary. It is one of the most famous commedie armoniche or commedie madrigalesche or again comedie musicali, as it is referred to in the preface to Orazio Vecchi's Amfiparnaso (1597). This genre enjoyed a certain popularity at the end of the sixteenth and into the third decade of the seventeenth century: Alessandro Striggio's Il cicalamento delle donne al bucato (1567) is usually cited as the first example, followed by works by Giovanni Croce, Orazio Vecchi and of course Banchieri. It is surely significant that these three musicians were all churchmen, for whom writing profane works must have been something of a diversion. It was a matter of producing straightforward, light-hearted entertainment, featuring settings not of the courtly, love-laden verses of the poets prized by the madrigalists of the day (Tasso, Guarini, Petrarca) but of lyrics they themselves composed or by minor provincial authors such as the Emilian Giulio Cesare Croce, famous for the adventures of Bertoldo. Commedie armoniche comprise a sequence of polyphonic pieces which may include madrigals but can also feature the villanella, giustiniana, moresca, canzonetta, intermezzo or simply free compositions rendering the comic spirit of an episode, frequently dance music with words added. Some of these comedies (like Banchieri's La Pazzia senile, 1598) have a story line linking one episode to another (in this case the love, first obstructed and then crowned with success, of the young couple Fulvio and Doralice, set against the senile concupiscence of Pantalone, duly mocked by the courtesan Lauretta), while others simply consist in a series of discrete cameos presenting particular situations or characters (as in Vecchi's Selva di varia ricreatione, 1590). In any case all are obviously a musical derivation of the commedia dell'arte, with the standard figures of the latter (Pantalone, Arlecchino, Dottor Graziano, the loving couple, the Spanish captain, and so on) recurring frequently. However, the commedia armonica was not intended to be staged, as is made quite clear in the prologue to the Amfiparnaso: "à this show I am speaking of is enjoyed in the mind's eye, being perceived through the ears and not the eyes". We can imagine a group of people gathering in a small, exclusive venue to sing these comic works either for their own enjoyment or to entertain a handful of friends who could conjure up the situations evoked by the songs "in the mind's eye". It was in fact a civilised way of passing an evening amongst friends, as is made explicit in the title of a comedy composed by Orazio Vecchi in 1604, Le Veglie di Siena, comprising games, imitations and other pastimes all set to music.

Banchieri's Festino presupposes a get together during the last days of carnival, actually before supper rather than in the evening, and in this case the musical diversions culminate in much hilarity around the dinner table. In the printed edition the introduction features an illustration showing an actor on stage and a view of streets and buildings in the background, with spectators crowding round the stage; the prologue to the Amfiparnaso has a very similar illustration. The guests, meaning the imagined spectators, are welcomed by the figure of "Modern Entertainment", and the contrast with "Antique Rigour" neatly represents Banchieri's propensity for the novel, light-hearted and eccentric as opposed to anything pedantic or aridly academic. We can recall that his Concerti ecclesiastici, 1595, was the first printed work to include the part of basso continuo, while he looked for inspiration to such original musical minds as Gesualdo, Viadana and Monteverdi. At the same time, however, these were the years in which accompanied monody was asserting itself, and with it the new genre of the melodramma, offering great flexibility and potential for characterisation on stage, since the characters could now be played by individual singers. For all his modernity, Banchieri did not take this direction. In the commedia armonica, in which a character was rendered by a polyphonic structure in three or five parts, it is impossible to create a scene with a character who sings his own text (although, as we have said, this was not the goal of these compositions).

In a world in which television has largely done away with the simple pleasures of an evening amongst friends, the question of how to perform these works has to be met with solutions that come as close as IX possible to the spirit of the composer. This was hardly the case of a vocal ensemble I can recall hearing some thirty years ago. The singers were drawn up in evening dress, each behind their own music stand, in rigorous observance of nineteenth century concert ritual, even as they were singing (in execrable German accents) zia Bernardina's fable of the magpie, culminating in the no nonsense "and a turd in your throat". Any attempt at a modern presentation must necessarily separate the musical and the dramatic dimensions. The singers, with the accompanying instruments, could be placed at the back of the stage or to one side, while actors could take centre stage, with or without dancers according to how many dance movements feature in the work being presented. The actors may either recite the lyrics or perform free improvisations on the contents of the successive pieces, ad-libbing in the manner of the commedia dell'arte and alternating with the music. The only contemporary indication we have is Banchieri's own suggestion for a realisation of La prudenza giovanile, 1607, in which he placed the singers at the back of the stage, with the actors occupying the proscenium, reciting the text before it was sung and then joining in the singing. Mimes, marionettes or puppets could be used instead of actors, accompanying the music and expressing the contents of the lyrics with their movements.

The successive episodes are written for two sopranos, contralto, tenor and bass. We can note that many of the contralto parts that do not go too high (as in Giustiniana di vecchietti chiozzotti) can be sung just as well, if not better, by a high tenor. We can also point out that since the two songs sung by the spinners (episodes XIV and XV) are notated in C clefs, it may well be appropriate to perform them as much as a fifth down, according to the desired effect and the available voices (a fifth down would necessarily involve a tenor rather than a contralto). Many of the episodes are suitable for performance by both individual voices and a choir, even though the madrigals are likely to be more expressive when sung by soloists. The first of the twenty episodes which make up the Festino is an invitation to all and sundry to stop and listen to the imminent entertainment. In the ensuing episodes facetious pieces, some with lyrics in dialect, alternate with madrigals on the theme of love. Most of the lyrics are by Banchieri himself but some are by renowned poets, such as "Ardo sì, ma non t'amo" and "Felice chi vi mira" by Giovan Battista Guarini. The madrigal "Bella Olimpia" refers to an episode in Canto X of Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso in which Bireno, having fallen in love with another woman, abandons Olimpia on an island. There are only a few proper madrigals treating of love, while many of the pieces actually send up the classical madrigal in one form or another. Thus we hear songs by old men from Chioggia, crippled by arthritis, and by buxom peasant women who hit wrong notes, a lute and an arpicordo, the dance rhythm of the Spagnoletto, the anecdote of the magpie who has been taught to repeat swear words, a counterpoint to a cantus fermus in macaronic Latin made up of the calls of an owl, a cuckoo, a dog and a cat, innuendoes concerning fine white spindles, all upstanding and turgid, or packs of matches ready to set fire to rags, the tongue twister of a children's game, the nonsense aria of the girl from Norcia (home to Saint Benedict, but famous for its hams), and the drunken solos in the final collective toast. Each new episode plays a part in desecrating the tradition of serious polyphony, nurtured by pedantic doctrine and evoking the veglia in which everyone present does a comic turn or tells a story until it's time for bed. At the end, an envoi that mirrors the opening invitation announces the forthcoming ublication of a new work, Il fior gradito, duly guaranteed to entertain listeners, but this work has not come down to us, and Banchieri may in fact never have written it.